SUSPENDED PHOTOGRAPHs

◇Chapter One: The Secret in the Drawer

November in New York was wrapped in a shrinking cold and dull gray that robbed one of hope. On a street lined with old brownstones in Prospect Heights, Brooklyn, Jacob Marshall stood with two suitcases and three cardboard boxes. At twenty-three, he was a graduate student studying art history at Columbia University. For him, barely scraping by on a scholarship and weekend shifts at a cocktail café, this furnished apartment was something of a luxury. At six hundred fifty dollars a month, it was a bargain by Manhattan standards.

At the property management office where he received the keys, a middle-aged female clerk told him expressionlessly.

"It's 3B on the third floor. There's no elevator. Please use the furniture as is. The previous tenant left it behind."

"Where did the previous tenant move to?" Jacob asked.

"I don't know. They disappeared suddenly. Without leaving any contact information."

The woman said nothing more and asked him to sign the documents.

The apartment was larger than expected. Past the entrance, there was a kitchen on the right and a bathroom on the left, with a living room and bedroom continuing beyond. The floor was old parquet with scratches here and there, but it looked like it would regain a rich luster if polished. The window offered only a view of the brick wall of the neighboring building, but the afternoon's slanting light cast soft shadows throughout the room. The furniture was surprisingly refined: a leather sofa, an old oak dining table, and in the bedroom, a bed frame adorned with brass decorations. And against the wall stood a heavy wooden chest with five drawers.

After putting down his luggage, Jacob decided to check every corner of the room. When he tried to open the chest's drawers, he felt a strange sensation. The bottom drawer wouldn't budge. When he pulled hard, it opened just slightly, as if caught on something. Reaching inside and groping around, he could tell something was wedged in the back of the drawer. What his fingertips touched had the texture of paper—an envelope.

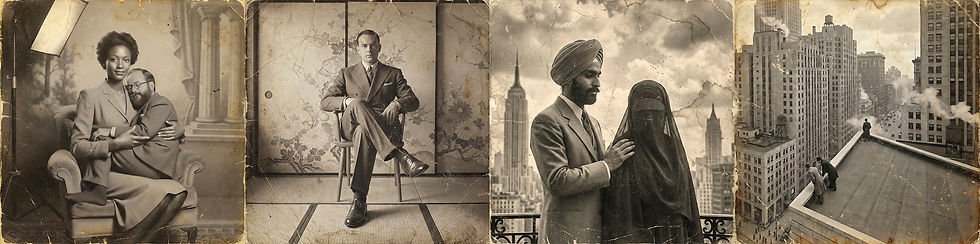

Jacob carefully extracted the envelope. It was an old envelope that had turned brown, unsealed, and he could tell something was inside. He placed the envelope on the table and removed its contents. What emerged were four aged photographs. The photographic paper had deteriorated considerably, but the images were well preserved.

The moment he saw the first photograph, Jacob caught his breath. It appeared to have been taken in a portrait studio. In the center, a beautiful Black woman sat in a leather chair alongside a small white man wearing glasses and a beard. She was tall with an elegant physique, dressed in a fine suit, her arms embracing the man. He rested his head on her shoulder, eyes closed, with a peaceful expression that nonetheless exuded vulnerability. The background lighting was innovative, and judging from their clothing, it appeared to be from the 1930s. In an era when racial discrimination was deeply rooted, what kind of relationship did these two have? Were they married, lovers, or complete strangers? The photograph conveyed something like love, yet also seemed staged. And at the same time, an indescribable tension permeated it.

And the second. This was a strange photograph. It was clearly a room in a Japanese house. Tatami mats were laid, and beautiful floral patterned sliding doors were visible in the background. In front of them sat a white man who looked like a corporate executive or diplomat, perched on a stool. He wore a suit, but hadn't removed his leather shoes—he sat with his legs crossed on the tatami while still wearing his shoes. An act of rudeness inconceivable in Japanese culture. Yet there was no sense of provocation or impropriety in the man's expression.

The third photograph captured an entirely different world. A rooftop of a high-rise building. Three men stood at the edge, looking down at the street far below. One wore a hat, another had his coat collar turned up. The third man had his back turned, gazing into the distance. There was tension in their postures. Were they searching for something, or fleeing from something? Detectives, or perhaps gangsters? The photograph offered no answers, conveying only an ominous atmosphere.

The fourth photograph showed what appeared to be an Indian man with his hand lightly placed on the right shoulder of a Muslim woman whose face was concealed by a scarf. The relationship between the two was difficult to imagine. The Empire State Building was faintly visible in the background of the photograph, though it was likely taken in a studio.

Jacob arranged the four photographs on the table. Each seemed to capture completely different scenes, yet he felt they were connected by some common thread. In any case, the quality of the photographs was extremely high—the composition, the use of light, the way the subjects were captured. These were not the work of an amateur. They must have been taken by the hand of a professional, a skilled photographer.

That evening, Jacob called the management office. The same unfriendly female clerk answered.

"I found something the previous tenant left behind," Jacob said. "Photographs. They might be important. I'd like to return them to the owner."

"That's impossible," the woman replied immediately. "As I've said repeatedly, we don't know their contact information. They were three months behind on rent and suddenly disappeared one day. Leaving most of their belongings behind."

"But these might have value."

"Anything that was in your apartment is now contractually yours. We can't store it. Do as you please."

The call ended. Jacob stared at the photographs again. Fragments of someone's life were here. Someone's memories, someone's secrets. And now they floated in a state of suspension in his hands.

◇Chapter Two: The Beginning of the Search

The next morning, Jacob headed to the university library. In the photography history section, he examined photography collections from the 1930s through the 1950s one after another. Robert Frank, Diane Arbus, Gordon Parks. But he found no works similar to those four photographs.

Early in the afternoon, Jacob visited the office of Professor Ellen Chang, who specialized in photography history. The professor, in her mid-sixties, looked at Jacob with sharp eyes behind her glasses.

"This is unusual, Jacob. For you to come here."

"I have something to consult about," he said, taking the photographs out of the envelope. "Do you know anything about these photographs?"

Professor Chang picked up each photograph, held them up to the light from the window, and observed every detail. A long silence followed.

"Wonderful photographs. Where did you get these?" the professor asked.

"I found them in the apartment I moved into. They seem to have been left by the previous tenant."

"Interesting." The professor arranged the photographs on her desk. "This is clearly professional work. The composition is too perfect. Especially this rooftop photograph. The arrangement of the three figures, the use of shadows, even the way depth is created."

"Who do you think made them?"

"I don't know." The professor shook her head. "But these are definitely works from the 1930s or 40s. Why don't you visit galleries in SoHo? Photography specialists might know more."

That weekend, Jacob ventured into Manhattan. He walked the cobblestone streets of SoHo, visiting galleries one by one. The first several turned him away. As the sun was beginning to set, Jacob stood before a small gallery. The modest sign read "Curtis Gallery." When he opened the door, a cowbell made a light sound. At a desk in the back, a white-haired man was looking through documents. Probably in his late sixties. He wore a navy suit with a neatly tied red tie.

"Welcome." The man lowered his reading glasses and looked up. His voice was gentle. "Please feel free to look around."

After surveying the photographs on the walls, Jacob approached the desk.

"Excuse me, I have something I'd like to ask about."

"Please do."

Jacob took the envelope from his bag and arranged the four photographs on the desk.

The man stood up from his chair and brought his face close to the photographs. Then suddenly, his movement stopped. His eyes behind the glasses widened.

"This is..." The man's voice trembled.

The man suddenly changed his expression and demeanor, even altering the way he spoke.

"Where did you get these?"

"I found them in the apartment I moved into."

The man picked up the first photograph with both hands and held it up to the ceiling light.

A long silence.

Jacob could see his hands trembling slightly.

The man looked at Jacob. His eyes held a mix of surprise and excitement.

"Whose work is this?" Jacob said.

But the man didn't answer. Instead, he opened a desk drawer and took out a checkbook. "I'll buy these four for a hundred dollars."

"What?"

"A hundred dollars. I can pay you in cash right now." The man looked into Jacob's eyes. "It shouldn't be a bad deal."

Jacob's heart raced. The photographs that other galleries had said were worthless—this man was trying to put a price on them.

"Whose photographs are they?" Jacob pressed. "Please tell me."

"I can't say."

"Why not?"

"That's the industry rule." The man ran his pen across the check. "A hundred dollars. Final offer."

"Let me think about it a bit more." Jacob put the photographs back in the envelope.

"Wait." The man raised his voice. "I'll give you two hundred per piece."

"Excuse me." Jacob headed for the door.

Behind him, he heard the man's voice. "You'll regret this!"

Jacob left the gallery. The night cold stung his cheeks. He tucked the envelope into his bag, clutched it to his chest, and hurried down the street. Conviction was beginning to sprout. These photographs might hold more mystery and value than he'd imagined.

◇Chapter Three: Edward Takahashi

Two weeks later, Jacob was holed up in the university library. This time he dug through archives of old photography magazines. He carefully turned the pages of issues from the 1930s through the 1950s, making sure not to miss anything.

And on the afternoon of the fourth day, Jacob finally found it. An issue of *Aperture* magazine from 1968. A photograph was published there. An old man standing in front of an abandoned factory. The composition, the use of light, the distance from the subject. It was remarkably similar to the photographs Jacob possessed. He read the caption. "Photograph: Edward Takahashi, 1937, Brooklyn." Jacob wrote the name in his notebook.

When he consulted with the librarian, she said there were almost no records remaining about Takahashi. Only this 1968 magazine article and a short article in the obituary section of the New York Times from 1970. The librarian set up the microfilm. The New York Times dated March 15, 1956. In the corner of the obituary section, there was a mere three-line article. "Photographer Edward Takahashi dies at age 72. Discovered dead in his Manhattan home, having died alone. Funeral to be held with close family only." That was all. He was treated like a person who had disappeared from this world without anyone knowing.

The next day, Jacob visited Curtis Gallery in SoHo again. This time he was armed. With information about Takahashi. When gallery owner David Curtis saw Jacob's figure, he smiled wryly.

"You came back after all."

"Those four photographs are by Edward Takahashi, aren't they?"

Curtis's expression changed. "You did your research well."

"Why didn't you tell me?"

"That's the rule in this industry." Curtis sighed. "When you buy from someone who doesn't know the value, you buy as cheaply as possible. That's business."

"Tell me about Takahashi."

Curtis sat down and motioned for Jacob to sit as well. Then he began to speak quietly.

"Edward Takahashi was a genius. But an unfortunate genius. He was active in New York from the late 1920s through the 1950s. He left many wonderful works, but was hardly recognized by society."

"Why?"

"Bad timing. His style was too far ahead of its time. And he was poor at socializing. He couldn't build relationships with galleries, couldn't market himself."

"I learned he died in 1956."

"Yes. It's said he was an alcoholic. In his last few years, he hardly took any photographs. And he died without anyone to watch over him."

Curtis looked out the window.

"But after his death, his work gradually began to be reevaluated. In the 1970s, several museums began collecting his work. In the 1980s, a small gallery in Brooklyn held a retrospective. And now, he's beginning to attract attention among photography enthusiasts as a 'lost master.'"

"So the photographs I have are...?"

"If they're truly unpublished works by Takahashi, they're worth quite a bit." Curtis looked straight into Jacob's eyes. "Only about a hundred of Takahashi's works are in circulation on the market. Meaning most of his works are still sleeping somewhere."

"How much are they worth?"

"Depending on condition, five to ten thousand dollars per piece."

Jacob gasped. Forty thousand dollars for four pieces. It was an amount beyond his imagination.

"Are you willing to sell?" Curtis asked. "This time I'll offer a fair price. Twenty thousand for all four. I can pay in cash immediately."

Twenty thousand dollars. An amount equivalent to Jacob's living expenses for a year.

But Jacob still couldn't give an answer.

"Let me think about it," he said.

◇Chapter Four: Takahashi's Footsteps

Jacob postponed his decision. Twenty thousand dollars was tempting, but something made him hesitate. He wanted to understand the photographs more deeply. He was becoming eager to know more about the person named Edward Takahashi.

On the weekend, Jacob headed to the Williamsburg area of Brooklyn. Late in the afternoon, Jacob found a small coffee shop and entered. At the counter stood an old man who appeared to be in his seventies.

"What'll you have?" the owner said.

"Coffee, please," he answered, then added, "Do you know of a photographer named Edward Takahashi? He should have been active around here in the 1930s."

The old man's hand stopped. Still holding the coffee cup, he stared at Jacob.

"Takahashi..." the old man whispered. "It's been a long time since I've heard that name."

Jacob's heart leaped.

"You know him?"

"Know him? Of course I do." The old man set the cup on the counter. "He was my friend."

The old man's name was Martin Cohen. He said he'd been active as a painter in the 1950s. And he belonged to the same artist community as Edward Takahashi.

"Edward was an odd one," Martin began.

The two sat at a table in the back of the shop.

"His photographs were edgy. Perhaps because of that, painters rather than photographers recognized his talent. But he seemed to refuse to be recognized by society—why, I wonder."

Jacob took out the envelope.

"Could you look at these photographs?"

He arranged the four photographs on the table. Martin put on his glasses and picked them up one by one. A long silence followed.

"These are..." Martin's voice trembled. "Edward's work. No doubt about it."

"How can you tell?"

"I can tell just by looking." Martin gazed at the first photograph of the Black woman and white man.

"This tenderness. This intimacy. Only Edward could capture this."

"Do you know these two people?"

Martin nodded.

"The woman's name is Elizabeth. Elizabeth Johnson. She was a teacher in Harlem. I don't know the man."

Jacob caught his breath.

"That's right." Martin continued to gaze at the photograph. "Edward may have loved Elizabeth. I believe it was around the end of the 1930s, but the two were never united."

Martin gently set down the photograph.

"Edward was crushed by the photography world. After that, he changed. Became more introverted, more solitary."

Looking at the fourth photograph of the three men on the rooftop, Martin laughed softly.

"I remember this one. It was around 1936, I think. We shot it on a building rooftop in Manhattan. I'm on the left, a friend is on the right. The one standing in the corner was a cool guy passing by who we invited for the shoot."

"What were the three of you looking for?"

"We weren't looking for anything," Martin said. "We were just gazing at the city. We were tense though. There was no special meaning."

And the second. Looking at the photograph of the Japanese house, Martin sighed deeply.

"This is from 1943. Edward wanted to go to Japan."

"Why Japan?"

"I don't know the truth. Probably it's related to the war. Perhaps he hated America's racist society and white people."

"Why is he on the tatami wearing shoes?"

"It's Edward's way of being ironic," Martin said with a laugh. "He was always rebelling against rules. This photograph may have been his own declaration. Something like 'I don't follow anyone's values.'"

Martin arranged the four photographs and gazed at them for a while.

"Where did you find these photographs?"

Jacob explained the situation. About the Prospect Heights apartment, the envelope wedged in the drawer, and the offer from Curtis Gallery.

"Curtis, eh?" Martin laughed bitterly. "He's always been like a hyena. Buy cheap and sell high."

"Do these photographs really have value?"

"For collectors, they're worth investing in," Martin answered. "Nowadays Edward's work is popular among some photography enthusiasts. Ironically, no one looked at it during his lifetime."

Martin wrapped both hands around his coffee cup.

"But the real value is elsewhere. These photographs are fragments of Edward's life. His irony, his dreams, his love. And loneliness. Selling these photographs means converting Edward's memories into money."

"What do you think I should do?" Jacob asked.

Martin was silent for a while.

"It's up to you to appreciate them, analyze them, and decide to sell. But I can say one thing. The frustration when you learn they're fake. Or conversely, learning they're genuine and converting them to money. That's fine too. But once you convert them to money, the story within you will disappear."

"Story...?"

"That's right. Judging from their deterioration, this quartet might be original prints made from the negatives."

That evening, Jacob sat before the photographs in his apartment. Martin's words echoed repeatedly in his head. These photographs certainly had their own story. Jacob decided. He wouldn't sell the photographs. Instead, he would investigate more, learn more. And he would search for the continuation of the story.

◇Chapter Five: The Lost Body of Work

The following week, Jacob headed to the Manhattan public records office. He researched Edward Takahashi's death records and estate records. According to the records, Takahashi was found dead in an apartment on the Lower East Side on March 11, 1956. The autopsy report stated "natural death due to alcoholic cirrhosis." The body had been left for three days.

The estate management records were simple. The estate consisted only of a small bank deposit and belongings left in the apartment. The total was less than five hundred dollars. The list of belongings noted "camera equipment, numerous photo negatives, numerous prints." But there was no record of where they had gone.

Next, Jacob examined real estate records from the Lower East Side around 1950. He identified the address of the apartment where Takahashi had lived and traced the building's owner at the time. The building had been demolished in 1972, but records of the landlord at the time remained. His name was Irwin Rosenberg. He would have been sixty-five in 1972.

With the kind cooperation of staff, he was able to locate Rosenberg's family. Following public records, it turned out that Rosenberg had one daughter. Rebecca Rosenberg Stein. She apparently now lived in Newark, New Jersey. Jacob found her number in the phone book and called.

"Hello?" An elderly woman's voice answered.

"Is this Rebecca Stein? I'm Jacob Marshall, a student at Columbia University. I'd like to ask about your father, Irwin Rosenberg."

There was silence on the other end of the line for a while.

"About my father? For what purpose?"

Jacob explained politely. That a photographer named Edward Takahashi had died in her father's apartment in 1956, that he was interested in his work. That if any memories or records remained, he would very much like to hear about them.

"Wait," Rebecca said. "Let me think about this."

Then she began to tell him something surprising.

"My father did own that apartment. I remember when Mr. Takahashi died. I was eighteen at the time."

"Do you know what happened to Mr. Takahashi's belongings?"

"My father was going to dispose of everything. But I stopped him. There were so many photographs, I thought they might be valuable."

Jacob's heart pounded violently.

"And then?"

"In the end, my father said he threw them away. But I rescued a few boxes' worth. Boxes containing old photographs and negatives. I just couldn't throw them away."

"Do you still have them?"

"Yes," Rebecca said. "They should be somewhere. I haven't looked at them in over fifty years."

"Would it be possible to see them?"

Rebecca hesitated a little. "Why are you so passionate about this?"

Jacob answered honestly. "Takahashi was a wonderful photographer. But he was hardly appreciated during his lifetime. Now his work is beginning to be reevaluated. If there are unpublished works in those boxes, it could be an important discovery in photography history."

"And it might be profitable for you...?"

Jacob was momentarily at a loss for words. But he couldn't lie. "Probably."

Rebecca laughed.

"You're honest. I like that. Fine. Come to my house this weekend. Let's look together."

On Saturday morning, Jacob headed to Newark. Rebecca Stein's home was an old single-family house in a quiet residential area on the city's outskirts. Rebecca was a woman in her mid-eighties, but she stood straight with a sharp gaze. She led Jacob into the living room and served him tea.

"My father died about twenty years ago," Rebecca said. "He was lucid until the end, but hardly talked about Mr. Takahashi."

"Why not?"

"I think my father felt guilty about the incident. If he'd noticed something was wrong earlier, he might have been able to save him."

The two descended to the basement. In the dimly lit space, old furniture and cardboard boxes were stacked haphazardly. Rebecca held a flashlight and proceeded deeper.

"I think it was around here."

After searching for about thirty minutes, Rebecca found a large cardboard box. On it was written in marker: "Takahashi 1956." When she opened the box, dust flew up. Inside were old envelopes and file holders, and hundreds of film negatives. Jacob gasped.

"This is..."

"Take it," Rebecca said.

"I don't need it. If you can use it for something good, that's best."

"But this might be valuable."

"That's exactly why." Rebecca smiled. "My father's guilt for not being able to do anything for Mr. Takahashi might be somewhat cleared by this."

Jacob brought the box back to his apartment. That night, he carefully checked the negatives one by one. There was Takahashi's lost body of work. So-called street photography. Children in Harlem, immigrants on the Lower East Side, factory workers in Brooklyn. Takahashi's camera captured the dignity of people who tended to be overlooked. Portrait photographs. The faces of nameless people. But every face seemed to be etched with the weight of life. And landscape photographs. Buildings that had become ruins, playground equipment left behind in vacant lots, old buildings before demolition. A record of a disappearing New York.

Jacob continued gazing at the negatives all night long. These must surely be the complete picture of Takahashi that no one had ever seen. But at the same time, Jacob worried. What should he do with these? If he brought them to Curtis Gallery, he could get a large sum of money. If he donated them to a museum, many people could see them. Or he might be able to hold his own exhibition.

The next morning, Jacob visited Professor Ellen Chang's office. The professor verified the negatives one by one. Using a loupe, holding them up to the light, observing every detail. It took three hours to check all the negatives.

"I can't judge," the professor said. "Whether these are all of Takahashi's work."

"What should I do?"

The professor pondered.

"First, these need to be properly preserved. The negatives are starting to deteriorate. You should request restoration from an expert."

"That will cost money."

"Yes. The university should probably support you. This could be an academically important discovery."

The professor stood up, crossed her arms, and looked at the ceiling. "Why don't you make this your research topic? Write a paper about Takahashi's work and life. That will become your master's thesis."

"But my specialty is the Renaissance."

"You can change your specialty." The professor smiled.

"This might be a chance to change your life, Jacob. Don't let it slip away."That evening, Jacob thought for a long time. Then he made his decision. He wouldn't sell the photographs. Instead, he would study them. Reconstruct Takahashi's life and make his work known to the world. It felt like a mission given to Jacob.

◇Chapter Six: The Road to the Exhibition

News that Edward Takahashi's body of work had been discovered spread faster than expected. It started when Professor Ellen Chang told a few of her colleagues at the university. A week later, there was a knock on Jacob's apartment door.

When he opened the door, an unfamiliar man stood there. Mid-forties, dressed in an expensive suit, carrying a leather briefcase.

"You're Jacob Marshall?" the man said. "I'm Robert Cain. I'm the vice president of Cain Auction House."

"How did you know where..." Jacob was wary.

"What do you want?"

"I heard you own unpublished works by Edward Takahashi. I'd like to talk to you about that."

"About what?"

"I have a wonderful proposal for you."

Jacob hesitated, but eventually let Cain in. The man sat on the sofa and opened his briefcase.

"I'll be direct," Cain said. "I'd like to feature Edward Takahashi's work in next spring's auction. The estimated total hammer price will be between five hundred thousand and one million dollars. We'll pay you eighty percent of that."

Jacob was stunned. "Eight hundred thousand dollars...?"

"That's a conservative estimate." Cain took out documents. "These are the past hammer prices for Takahashi's work."

The documents showed astonishing figures. In recent years, the value of Takahashi's work had skyrocketed. A work that was three thousand dollars five years ago was now trading for twenty thousand.

"Why has the value risen so much?"

"Because he's a rediscovered master," Cain explained. "Art historians are beginning to recognize his importance. Major museums are starting to collect his work. And above all, Takahashi's work is rare."

Jacob's heart wavered. Eight hundred thousand dollars. An amount beyond his imagination.

"Let me think about it," Jacob said.

"Of course." Cain left his business card. "But I can't wait too long."

After Cain left, Jacob stared at the business card, feeling anxious about what was to come. That premonition proved correct. The next day, there was a call from another auction house. The day after that, a gallery owner visited. All made similar offers. Six hundred thousand, seven hundred thousand, nine hundred thousand. The numbers continued to jump.

And a week later, there was a call from David Curtis.

"I heard," Curtis's voice was cold. "Looks like you caught a big fish."

"It seems the rumors are spreading."

"It's a small industry." Curtis said. "Everyone knows what you have. And everyone's trying to use you."

"You're the same, aren't you?"

Curtis laughed. "Well, don't say that. But I'm honest. I told you from the start this is business."

"So, what do you want?"

"Advice." Curtis's voice became serious. "Don't be fooled by those auction house people. They promise high amounts, but the actual hammer price often falls below estimates. Plus they take a twenty percent commission. Then there's restoration costs, catalog production costs, insurance fees... you'll pay all of it."

"Meaning?"

"Meaning when they say eight hundred thousand, only half of that might end up in your hands."

Jacob fell silent. Though it didn't really matter.

"I have a proposal," Curtis said. "Sell the work to me. Four hundred thousand dollars in cash right now. No commission, no expenses. It's all yours."

"That's less than the others."

"But it's certain." Curtis said. "I have cash. I can pay today or tomorrow. No risk, no waiting."

After hanging up, Jacob sighed deeply. Who and what should he trust?

That evening, he headed to Martin Cohen's coffee shop again. The old painter stood behind the counter as always. Jacob told him about the events of the past week. The offers from auction houses, Curtis's warning, and his own confusion. Martin listened silently.

"What would Edward think if he were alive?"

"What do you mean?"

"Edward didn't take photographs for money. At least not entirely." Martin continued. "He took them to make people feel something. People's dignity, social injustice, the beauty of a disappearing world. His work was always in a suspended state, but..."

"But he was poor. He wasn't recognized," Jacob said.

"That's right." Martin nodded. "But that was also his choice. He refused to compromise."

Martin poured coffee.

"If you sell his work now for hundreds of thousands of dollars, you'll be accepting what Edward kept refusing. You'll turn his work into merchandise."

"Then what should I do?"

"That's for you to decide." Martin said. "But I can say one thing. Money is a means, not an end. And money is not substance—it's illusion."

Jacob couldn't answer.

When he returned to the apartment, he stared at the four photographs again. The photograph of Elizabeth embracing the small man. The man wearing shoes in a Japanese house. The Indian man and the Muslim woman. The strange trio on the rooftop. Quest and solitude. In that moment, Jacob made his decision. And the next morning, he called Robert Cain.

"I'm declining the offer," Jacob said.

"May I ask why?" Cain sounded surprised.

"I don't want to sell the work. Instead, I want to hold an exhibition."

"An exhibition?"

"A retrospective of Takahashi. An exhibition comprehensively introducing his life and work. I think that's the right way to show respect for his work."

"That might not be a bad idea. But it takes money to hold an exhibition."

"I know." Jacob answered. "But I'll make it work."

After hanging up, Jacob contacted Professor Ellen Chang. When the professor heard his plan, she immediately agreed.

"It's a wonderful idea." The professor said. "I might be able to arrange for you to use the university gallery. And I think I can help with grant applications."

Over the following weeks, Jacob immersed himself in preparing for the exhibition. First, he commissioned experts to restore the negatives. Using the university's budget, he was able to restore the fifty most important pieces. Next, he deepened his research into Takahashi's life. He sought out people who had once been involved with Takahashi and interviewed them one by one. Most agreed to video recording.

Through these interviews, Jacob began to grasp the full picture of the person named Edward Takahashi. A talented photographer, but a person tormented by anxiety and fear. A life seeking love but unable to accept it. And he realized that all of this was reflected in Takahashi's work. He developed a plan for the exhibition's structure.

Section One: "Love and Separation" - Works centered on his relationship with Elizabeth Johnson.

Section Two: "A Disappearing City" - Records of New York being lost to redevelopment.

Section Three: "Overlooked People" - Portraits of workers, immigrants, and children.

Section Four: "Dreams of the East" - Works in a Japanese style.

Section Five: "Solitary Later Years" - Takahashi's last works from the early 1950s.

The next task was producing the catalog.

"You'll write it," Professor Chang said. "That will become your master's thesis."

Jacob continued writing late into the night. He traced Takahashi's life, analyzed his work, and discussed his artistic contribution. He rewrote many times, reread many times. And in March, the catalog manuscript was completed. A comprehensive research result about Takahashi spanning a hundred pages.

However, as the exhibition opening approached, an unexpected problem surfaced. One day, Jacob received a letter from a lawyer. The sender's name was "Michael Takahashi Law Office."

When he opened the letter, it contained shocking content. He froze.

"Dear Mr. Jacob Marshall,

I am the representative of Michael Takahashi, nephew of Edward Takahashi. Regarding the works by Edward Takahashi that you own and are attempting to exhibit, we assert legal rights. These works are part of Edward Takahashi's estate and belong to my client, the rightful heir. We demand immediate cancellation of the exhibition."

Jacob gripped the letter. A nephew? Did Takahashi have family? He immediately contacted Professor Ellen Chang. The professor consulted with the university's legal department and had them investigate the situation.

Three days later, there was a report from the legal department.

"Michael Takahashi is a real person," the university's lawyer explained. "He's the son of Edward Takahashi's younger sister. But there's a problem. The inheritance procedures at the time were incomplete. Legally, estate disposed of as owner-unknown may become the property of the finder."

"Meaning?"

"It's a gray zone," the lawyer said. "If it goes to trial, we don't know who would win."

Jacob despaired. After coming this far—

That evening, there was a call from David Curtis.

"I heard," Curtis said. "About the Michael Takahashi matter."

"How do you know?"

"I told you the industry is small." Curtis laughed. "So what are you going to do?"

"I don't know."

"Negotiate with him," Curtis said. "Meet Michael Takahashi directly and find out what he wants."

"Will you help negotiate?"

Curtis was silent for a moment.

"All right. Fine. One condition. If the exhibition is successful, give me priority rights to sales of the work afterward."

"Let me think about it."

The next day, Curtis and Jacob visited Michael Takahashi's law office. It was on the thirtieth floor of a high-rise building in Midtown.

"Quite a high-earning lawyer," Curtis said.

Michael Takahashi was a lean man in his late forties wearing an expensive suit. Sharp eyes, a firmly set mouth.

"I'll be direct," Michael said. "You stole my uncle's work. I want them back."

"I didn't steal them," Jacob answered.

"I obtained them legally and legitimately."

Curtis intervened.

"Michael, what is it you want? Money?"

"Not money," Michael answered immediately. "I want to protect my uncle's honor."

"Honor?" Curtis asked back.

"My uncle suffered during his lifetime," emotion entered Michael's voice. "He wasn't recognized by anyone and died in poverty. And after his death, his work is being made an object of speculation. I can't stand it."

Jacob was surprised. Michael wasn't after money.

"I feel the same way," Jacob said. "That's exactly why I want to hold an exhibition. To properly evaluate Takahashi's work and record his life. That's the purpose of the exhibition."

Michael scrutinized Jacob. After a pause, he said.

"Tell me about the exhibition's content."

Jacob took out the catalog draft. Michael carefully read through it page by page. Thirty minutes passed. Then he looked up.

"Not bad," Michael said. "No, it's well done. You're trying to understand my uncle."

"Thank you for understanding."

"I have conditions," Michael said. "I'll cooperate with the exhibition too. I'll provide memories of my uncle and family photographs. Part of the exhibition's proceeds must be donated to an arts support foundation bearing my uncle's name."

"Gladly," Jacob answered, then turned to Curtis.

"Is that acceptable?"

"Of course."

The three shook hands. The crisis was averted.

◇Chapter Seven: The Exhibition's Success and the Auction

The exhibition's opening was set for May. A three-week run at the university gallery. With Michael Takahashi's cooperation, Edward Takahashi's family photographs and personal effects would also be exhibited. A week before the opening, Michael brought an old album.

"These are photographs of my uncle when he was young," Michael said.

When he opened the album, there was a young Edward Takahashi. In his twenties, thin but brimming with vitality. Posing with a camera, laughing with friends.

"This is..." Jacob pointed to one photograph. There was Edward Takahashi photographing in a room like a Japanese house.

"Where was this taken?"

"I heard it was Little Tokyo in Los Angeles," Michael answered.

"Why did he take these photographs?"

"I don't know."

In Jacob's mind, pieces of the puzzle began to crumble. Those four photographs. Were they all related to Takahashi himself? But why were those photographs hidden in—or left in—the drawer in Jacob's apartment?

The night before the exhibition opened, Jacob called the management office again. This time he pressed hard. "Tell me about the previous tenant. Just the name."

The clerk reluctantly answered. "His name was Leon Schmidt."

Jacob wrote the name in his notebook.

That night, he searched the name online. One name surfaced. Leon Schmidt's profession was "photograph restorer."

The next day, Jacob headed to the Manhattan Photography Association.

"Oh, Leon," an elderly female clerk said. "He was a wonderful restorer. I heard he retired a few years ago and moved somewhere."

"Did he know Edward Takahashi?"

"Yes, Leon was one of Takahashi's enthusiastic fans. Even after Takahashi died, he was trying to preserve his work."

Jacob's heart leaped.

"Do you know how to contact him?"

"Wait, I'll look it up."

After a few minutes, the woman gave him a phone number. A Florida number. Jacob called immediately. After several rings, an old man's voice answered.

"Yes."

"Is this Leon Schmidt?"

"—Yes."

"I'm Jacob Marshall. I'm living in the Brooklyn apartment where you used to live."

On the other end of the line, he heard a sharp intake of breath.

"I found four photographs in a drawer. Do you know what they are?"

A long silence followed.

"Takahashi's photographs—they were there?" Leon's voice trembled.

"Yes."

"Thank goodness." Leon sighed with relief.

"I thought I'd thrown them away with the garbage."

"Did you leave them there?"

"I looked for them but couldn't find them," Leon explained. "I was in a hurry during the move, and didn't notice they were wedged in the back of the drawer. By the time I realized it, I'd already returned the keys."

"Can you tell me about these photographs?"

Leon began to speak.

"Those three, I didn't know if they were genuine or fake. So I did nothing."

"Genuine or fake?"

"Yes, that's right."

"Why those four?"

"Because I thought each represented a turning point in Edward's life."

"But why did you hide them?"

"I wasn't hiding them. I was storing them." Leon said. "But as I got older, my memory became vague. In the confusion of moving, I must have forgotten where I stored them."

Jacob took a deep breath.

"Actually, I'm preparing a retrospective of Edward Takahashi. Tomorrow is the opening."

"I see." A shadow mixed into Leon's voice.

"I'd like to exhibit those four as well. Would that be all right?"

"That's fine."

The exhibition was a great success. From the first day, long lines formed. Art critics, photographers, students, general visitors. Everyone was fascinated by Takahashi's work. A critic for the New York Times wrote: "Edward Takahashi was a forgotten master. But now his work speaks to us. About human dignity, social injustice, and the permanence of art."

During the run, Jacob was at the gallery every day. He conversed with visitors, answered questions, talked about Takahashi's life. Every time he saw people's reactions, his conviction deepened. This was the right choice.

But on the exhibition's final day, an unexpected event occurred. An hour before closing, a man entered the gallery. Mid-sixties, wearing an expensive suit, accompanied by a woman. The man carefully appreciated each work one by one. When Jacob approached, the man turned around.

"A wonderful exhibition," the man said. "Did you plan this?"

"Yes, I'm Jacob Marshall."

"I'm Peter Harrison." The man offered his business card. "Director of the Harrison Collection."

Jacob looked at the card and gasped. The Harrison Collection was one of the world's most important photography collections.

"Actually, I have a proposal," Harrison said.

"I want to buy all the works on display here."

"All of them?"

"Yes. Including the three hundred unpublished works. I want to add them to our collection."

"For how much...?"

Harrison handed him a paper with a figure written on it.

Jacob couldn't believe his eyes.

"One and a half million dollars..."

"However, there's a condition," Harrison continued. "These works will be loaned to museums around the world as part of our collection. Takahashi's name will be remembered forever."

Jacob couldn't answer. One and a half million dollars. An amount that would fundamentally change his life. He needed to consult with Michael Takahashi and Curtis.

"Let me think about it."

"Of course." Harrison smiled. "But I can't wait too long. I'd like an answer by Monday."

That evening, Jacob called Michael Takahashi. When he explained the situation, Michael said:

"The decision is yours. But if you want my opinion, you should sell."

"But I'll be giving up the works."

"So what?" Michael said.

"You've done enough for my uncle. You'll make his name known to the world and have it properly evaluated. That's enough. From now on, you should think about your own life."

Jacob also consulted with Martin Cohen. After listening while quietly making coffee, the old painter said:

"Edward didn't seek money. But that doesn't mean money was unnecessary. He suffered from poverty, and it eroded his life. If he'd had financial comfort, he might have lived longer and left more work behind."

"Meaning...?"

"You're still young. Your life is ahead of you. Use this money to do something meaningful. Continue your research, discover other forgotten artists. Shine a light on people like Edward. That's the greatest respect you can show Edward."

After that, he also called Curtis.

"If it's Peter Harrison, you can trust him," Curtis said only that.

Over the weekend, Jacob examined the four photographs repeatedly in his apartment. Rain was falling outside the window. Elizabeth embracing the small man. The man wearing shoes in a Japanese house. The Indian man and the Muslim woman. The strange trio on the rooftop. Quest and solitude. These photographs might no longer be his. But that was all right, he thought. Photographs are just objects. What matters is what they convey. And that something had already reached many people.

On Monday morning, Jacob called Peter Harrison. "I accept the offer," he said.

◇Chapter Eight: The Auction's Surprise

The contract proceeded quickly. Harrison Collection's lawyers prepared the documents, and the university's legal department verified them. Michael Takahashi also agreed to the contract, and it was decided that part of the proceeds would be donated to an arts support foundation.

In early June, the contract was completed. One and a half million dollars was deposited into Jacob's bank account. Of that, three hundred thousand dollars went to Michael Takahashi's share, two hundred thousand to Curtis, one hundred thousand to the university as thanks, and fifty thousand toward exhibition expense settlement. For the first time, Jacob obtained true financial freedom. He paid off his student loans. He sent fifty thousand dollars to his parents and carefully invested some of the remainder.

Summer arrived. Jacob submitted his master's thesis and graduated with excellent grades. His thesis "Edward Takahashi: The Rediscovery of a Forgotten Photographer" won the university's best thesis award. And in autumn, Jacob decided to continue to a doctoral program. The theme: "Twentieth Century American Photography History." Particularly the excavation and research of forgotten photographers like Takahashi.

Jacob's life seemed to be progressing smoothly. But the story wasn't over yet.

One day in September, there was a call from David Curtis.

"Did you see it?" Curtis's voice was excited.

"See what?"

"This morning's New York Times. Look at it right now."

Jacob rushed to buy the paper. A large headline on the arts page jumped out at him. "Edward Takahashi's Unpublished Works Fetch Eight Hundred Thousand Dollars at Auction."

As he read on, astonishing content was recorded. "Last Friday, at an auction held by Cain Auction House, four unpublished works by photographer Edward Takahashi sold for eight hundred thousand dollars, far exceeding estimates. The works all appear to be from the 1930s to 1940s and were not displayed in the retrospective held this spring."

Jacob was confused. Unpublished works? He should have sold all the works he had to the Harrison Collection. The article included photographs. When he saw them, Jacob froze. There were the same four photographs he'd had.

The photograph of Elizabeth embracing the man. The man in a Japanese house. The Indian man and the Muslim woman. The three men on the rooftop. But the condition of the photographs lacked the antiquity and was different. The four deteriorating photographs Jacob possessed were exhibited. But they weren't included in the Harrison Collection. The four deteriorated ones were owned by Leon Schmidt. Jacob opened the drawer, and there were indeed four photographs there. So what had been auctioned?

He called Cain Auction House. The receptionist answered.

"I'd like to inquire about last week's auction."

"Yes, how may I help you?"

"About the Edward Takahashi quartet... are those original prints?"

"Please wait a moment."

After a few minutes, a different voice came on the line. It was Robert Cain.

"Jacob Marshall. Long time no see."

"I'd like to ask about those four photographs."

"That involves confidentiality," Cain said. "I can't reveal the consignor's name."

"But they're the same as the photographs I found."

"The same? What are you talking about?" Confusion mixed into Cain's voice.

"The photographs you found should be in your possession. The ones at the auction were from a different consignor."

"But the composition and subjects are exactly the same."

"That's..." Cain hedged. "They were probably printed from the same negatives. Takahashi sometimes made multiple prints from the same negative. So the value changes depending on the photograph's condition and nature."

After hanging up, Jacob thought deeply. Multiple prints from the same negatives. Like woodblock prints, it was theoretically possible. But who had possessed those prints?

That evening, Jacob called Leon Schmidt.

"How many prints did you make of those four photographs?"

"I don't have the film."

"Meaning you didn't print them?"

"Of course not."

"What happened to the negatives?"

"Edward should have had them," Leon said. "After his death, the negatives are supposed to have been disposed of by the apartment landlord."

Jacob considered another possibility. What if some negatives had escaped disposal?

The next day, he called Rebecca Stein in New Jersey.

"Besides that box, were there really no other belongings of Mr. Takahashi's?"

"I don't think so..."

Rebecca pondered.

"Wait. Come to think of it, my father had a small safe. I think he said he put some of Mr. Takahashi's things in there—"

"Do you still have that safe?"

"It should be. Somewhere in the basement."

On the weekend, Jacob visited Newark again. Searching the basement with Rebecca, they found an old metal safe. Two days later, a locksmith opened the safe. Inside were several old envelopes and a small box. When he opened the box, dozens of film negatives were inside. And in the envelope, there was one letter. The letter was from Irwin Rosenberg to Rebecca. Dated March 1956.

"Dear Rebecca,

I've cleared out Mr. Takahashi's apartment. I disposed of most things, but saved just a few negatives. I thought they might be valuable someday. When I die, you can decide what to do with these."

With trembling hands, Jacob checked the negatives. Among them were the negatives from which those four photographs had been printed. And at the bottom of the envelope, there was another slip of paper.

"Edward Takahashi's negatives. March 15, 1956, stored by Irwin Rosenberg. August 1982, duplicate prints sold to David Curtis."

Jacob understood everything. Curtis had bought prints from Rosenberg in 1982. But at the time they were worth next to nothing. And this year, perfectly timing Takahashi's soaring value, he put them up for auction.

Jacob headed to Curtis Gallery. He opened the door, trembling with anger.

Curtis sat at his desk. When he saw Jacob's figure, he smiled resignedly.

"You finally figured it out."

"You knew from the beginning," Jacob said. "That you also had the same photographs I possessed."

"That's right," Curtis admitted. "I bought prints from Rosenberg in 1982. But at the time they were worth next to nothing. Nobody knew Takahashi."

"And you set me up. You had me hold an exhibition and drove up Takahashi's value."

"Set you up? Don't be ridiculous." Curtis laughed. "You decided on the exhibition yourself after consulting with your professor. I just gave advice."

"And you put the works up for auction at the perfect timing."

"That's business," Curtis's eyes were direct. "I held those photographs for twenty-five years. And I waited for the best moment. Thanks to you, Takahashi's market value rose. I'm grateful."

Jacob clenched his fists.

"You..."

"Don't be so angry." Curtis said. "You got a lot of money. I got money. And Takahashi's name spread. Nobody lost, right?"

"Nobody lost?"

"That's right." Curtis stood up. "You're an idealist, Jacob. You're sincere and beautiful. But the real world doesn't move on ideals alone. I'm a legitimate art dealer. My job is to make money. And that's not a bad thing. I'm making my own contribution to society."

Jacob couldn't say anything. Curtis's words were cold, but they struck at a certain truth.

"Do as you like." Curtis said with a smile. "And you keep pursuing your ideals. But don't forget. This industry is always swinging between money and art. You'll face that reality eventually too—I think you already have."

Jacob left the gallery. Outside, dusk was approaching and streetlights were beginning to glow. As he walked, he reflected on the events of these past months. The discovery of the four photographs by Schmidt. The quest surrounding Takahashi's life. The exhibition's success. And the unexpected auction. Everything was intricately intertwined. Good intentions and desire. Ideals and reality. Art and commerce. And now, Jacob understood. There is no clear ending to the story.

As autumn deepened, New York entered the season of autumn leaves. Jacob attended doctoral program lectures and worked on new research themes. Besides Edward Takahashi, there were many forgotten photographers. He was trying to dig up their stories one by one.

Why were those four photographs in the drawer? Did Leon truly forget them by chance, or did he intentionally leave them? Is Curtis still hiding something? And the many memories Michael Takahashi didn't speak of. About Elizabeth Johnson. There would probably never be answers to those questions. But that was all right, Jacob thought. Perfect stories don't exist. Stories where all answers are revealed don't exist in reality. Life continues in a state of suspension. Carrying unsolved mysteries, moving on to the next chapter. Just as Edward Takahashi's life was. Just as Jacob's life will be. And this story too—

The End

Author : Keisuke Togawa